Ideas on Myth, Truth, the ‘Other’, and the Inside-Outside Tension (WARNING: SPOILERS)

May 11, 2012 Leave a comment

WARNING: THIS POST CONTAINS PLOT SPOILERS. IF YOU DO NOT WANT TO KNOW HOW THE PLAY ENDS, DO NOT READ BEYOND THIS POINT.

Here I’ll address some of the heavier, abstract concepts that formed a good deal of the last few weeks of my research.

First, a few words on myth. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, myth is “a traditional story, typically involving supernatural beings or forces, which embodies and provides an explanation, aetiology [cause], or justification for something such as the early history of a society, a religious belief or ritual, or a natural phenomenon.” According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, it is “a symbolic narrative, usually of unknown origin and at least partly traditional, that ostensibly relates actual events and that is especially associated with religious belief… Myths are specific accounts of gods or superhuman beings involved in extraordinary events or circumstances in a time that is unspecified but which is understood as existing apart from ordinary human experience.”

Breaking that down a bit, HE has elements of a myth, but is not strictly a myth per se; one can argue that HE is a God-like figure and that his arrival at the circus is an extraordinary event indeed, given that the play itself fits under the escapist subset of Neo-Romantic plays that are set in otherworldly or exotic locations in another time. The play is set in France in a prior century, but the realism of the play is such that one can’t quite qualify it as ‘existing apart from ordinary human experience.’

WARNING: REALLY, IF YOU DON’T WANT TO KNOW HOW THE PLAY ENDS, STOP READING IMMEDIATELY. PLOT SPOILERS BELOW.

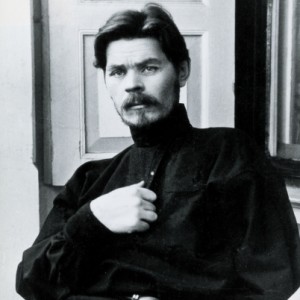

The critic Harold Segel finds much in HE that is mythical, pointing out the end as the play’s mythic substructure now made over-structure (that is, it dominates rather than hides) – death, last words, challenge flung, action moved to a metaphysical plane (that is, the afterlife). But, there is more just under that surface. Recall Consuela as Psyche, and HE as ‘an old god in changed garb’ come to Earth to rescue her, the goddess born of sea-foam much like Venus. While this element has been largely struck from the present adaptation, it is still important to keep it in mind; this very idea of HE as a self-made god coming from the outside into a foreign world brings to mind a short story by Fyodor Dostoevsky – author of Crime & Punishment – called “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”. (Dostoevsky, by the way, was quite an influence on Andreyev; Andreyev wrote in 1910 “Of past Russian writers Dostoevsky is closest of all to me. I consider myself his direct pupil and follower.”)

In”The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”, the protagonist describes a dream in which he infiltrates a society that lived more or less as a collective; all actions were performed for the benefit of the group, and the pronoun ‘I’ had no place among the people – all were one, and one was all. As soon as the protagonist enters the society and introduces the idea of an individual ‘I’ – he begins telling everyone that their way of life is false and only he has possession of The Truth – the society begins to break down; sin is committed, crime flourishes, and the happiness of the population is destroyed. The protagonist sees that he is responsible for this and asks the people to crucify him for his transgression, begging to be made a martyr. They refuse to kill him and instead take him to an insane asylum, at which point he wakes up from the dream.

HE echoes this story in that He, an outsider, comes into a world that operates under its own customs and laws and demands to be made part of it. In this way he is a self-made god, and a Christ-like figure whose purpose is not ascertained for some time after his arrival. Ultimately his arrival causes the disintegration of most of the world that he enters; he gets to leave it, but not as a martyr, and the reader never finds out what becomes of the rest of the characters. It is as if the reader is watching someone else’s dream of a ridiculous man, except the reader does not get to see him wake up.

Does He have the truth? The reader never finds out, because Andreyev ends the play with He taking his own life, thereby denying the reader a chance to see what happens in His wake. Raising this question is, however, a good segué into the idea of ‘the other’, because He is very much an ‘other’ who, in turn, raises questions of inside vs. outside.

Much has been written elsewhere – and on this resource guide – about Andreyev’s relationship with Gorky, which has been characterized as the relationship of a shadow to its caster; Andreyev was Gorky’s shadow, and then Gorky became Andreyev’s shadow, which the reader sees reflected in the relationship between He and the Gentlewoman. From the outset, it is clear to the reader that He is an Other; he doesn’t fit in with the circus at all, and has to ask to be made into one of them, which is a humbling and potentially humiliating experience – after all, the performers could have said ‘no’. HE immediately violates group protocol by refusing to play by its rules and learn its inner workings and dynamic, almost gleefully violating the rules before he’s even learned them, though he does submit to the self-conceived act of being slapped. Yet even when He is considered one of the group, He is still an Other – he gets special treatment and is allowed to get away with violating the group norms, which threatens people such as the Baron, who perhaps senses that this Other is indeed a dangerous being.

But why introduce this character of the Other in the form of He? James Woodward describes Andreyev’s career in elementary school thus: “Andreyev balked from the beginning at this fetish for rules and regulations, of which he was subsequently to deliver scathing indictments in his early feuilletons… He stood out against the grey student mass as a graphic protest. ‘His gloomy, proud appearance, for which his comrades nicknamed him so aptly the duke, his love of solitude, his contemptuous attitude to his studies… and to the rules and teachers, which expressed itself in everything, beginning with his persistence in wearing his hair long, which was persecuted and punished by the authorities – all this sharply singled him out.’” Perhaps, then, there is an autobiographical element to the play deeper than that of the shadow/caster relationship between Andreyev and Gorky; here we see Andreyev in his youth as a self-made Other, much like He. But later in his career, it did not escape the notice of critics that Andreyev could not detach himself from his heroes; Woodward says that “the imprint of his own sufferings is clearly stamped on those of his protagonists… the fiction of Andreyev is not only an indictment of the world in which he lived; it is also a work of self-castigation.” One of the indictments he made of his world was the “problem of individual isolation”, which we can maybe stretch to include self-made Others, who choose to isolate themselves and, perhaps, thus elevate themselves above the rest of society. HE is a bit late in Andreyev’s body of work to be really considered part of his literary attacks on solitude, but the echo is unmistakable: an individual who has removed himself from one society and thus isolated himself is a danger not only to himself but also to any other society with which he comes into contact. (Recall that Andreyev spent the last few years of his own life in solitude in Finland, which essentially destroyed any remaining relationships he had.)

This, of course, brings up the great tension in HE of ‘inside’ versus ‘outside’, which can be extended to include the internal vs. the external as well. Harold Segel wrote that Symbolist drama of Andreyev’s time “sought to shift emphasis from the external to the internal, which was now invested with a far greater and more universal significance… This intense preoccupation of symbolism with death led to a corresponding deemphasis of man’s physical life… the drives and ambitions of the physical life become ultimately inconsequential in the face of death.” It also has to “reflect [the spiritual core of the work] by pointing up the insignificance of the mundane before the awesome infinitude of the supernatural and structurally by either eliminating or greatly minimizing external action.” The reader sees this in HE with the outside world from which He comes being painted as almost evil, and the focus of the action instead is on the inside of the circus ring, on this inner world to which so few have access (so, in a sense, it becomes a sacred space just waiting to be violated). This inner world, recall from Segel, serves on its surface as a refuge of escape for He because He initially finds solace in this new world until the wonderfully ironic moment of yet another Other from the outer world intruding (and recall Segel interpreting this as Andreyev’s indictment of the very idea of escape – ultimately, it is futile, because whatever you’re running from will eventually catch up to you). It is no coincidence that poison is involved in the death of both Consuela and He, because the outer world itself is poison to both the play’s characters and Andreyev himself.

This idea of an inner and outer world could be related to Andreyev’s preoccupation with two planes of existence, an idea that he cultivated early on in his writing and that was time and again expressed throughout his career. Woodward notes that his works from the start “show a dualistic conception of reality… [this preoccupation] with this distinction between two realities, two levels of life, is confirmed not only by his fiction, but also by numerous passing remarks in his correspondence.” One of these remarks refers to a “first reality” which Woodward classifies as “employed by Andreyev to denote the ephemeral, the world of man’s empirical existence… On this plane man is a prisoner within the walls of his individuality, and his intellect is the instrument by means of which he endeavors to pierce them. But its struggles are eternally frustrated; its powers do not extend beyond the ‘first reality’. The whole impetus of Andreyev’s thought is towards the establishment of contact with the ‘other plane’, the transcendence of the empirical ego.” One can translate these two planes of existence into inner and outer; the inner world, the sacred space, is the ‘other plane’ towards which the reader – and his protagonists – must strive, and the outer world, the ‘first reality’, is the poisoned space from which the reader – and his protagonists – must escape.

Considering Andreyev’s background with depression, this idea of a dual life – inner and outer – makes perfect sense. Mental illness was a large part of the writer’s life; in the diaries he kept through 1909, Andreyev projected both an internal and external ‘I’, as the critic Frederick White notes. This could well have translated later into Andreyev’s keen desire to keep his depression a secret; recall that he very much wanted no one outside of his family and close friends to know that he was depressed (and even that is debatable, since he would let them know he wasn’t feeling well but would tell them that it was physical, and not mental!), and that he did not take kindly to anyone saying he – or any of his characters, many of whom critics pegged as autobiographical – had gone insane. As he gained popularity, he found himself increasingly the subject of scrutiny and criticism, which he did not appreciate; he struggled greatly to control how he was portrayed in the public eye – that is, how his outer self was perceived by others. The Russian writer Georgy Chulkov notes this ‘double life’ of Andreyev, in which “on one side was a large family, many acquaintances, publishers, critics, reporters, actors, and an endless procession of chance visitors: which means a lot of concern and fuss. On the other side, there was his internal excruciating anxiety, blind and grim, which tormented him: here, in solitude, his soul consumed itself.”

From this it is clear that at play is a conflict of inner and outer lives and selves; in his own world, Andreyev had an internal self, one that he would not show to the outside world for fear of having it poisoned somehow by that world. (This also brings to mind his reaction to the first performance of HE in Moscow, when he complained that they – the director and actors – had ruined his play; the outside world had intruded on his inside world, which existed only on the page until that point, and corrupted it irreparably!) He thus had to fashion an outer self – a shell – to present to the outside world in order to protect his inner self from this poison. This outer self became more solidly formed after Gorky’s constant rebuffs of his desire for deep friendship; having offered Gorky his inner self, and having had it rejected, he had to work harder at cultivating an outer self for both Gorky and the public at large. Ultimately, when he found himself no longer able to live in the outer world – the ‘first reality’ – Andreyev retreated into an inner world of isolation in Finland, training his gaze inward when an outward look would no longer fulfill him.

The reader sees what happens in HE when inside and outside meet – to understate, Very Bad Things. But can one argue that there is some good that comes out of this conflict? HE – and He – does force the reader to confront questions of loss, love, betrayal, life, death, and so forth, and none of these questions would even exist without the simple introduction of an Other – an Outsider – to an inside space whose inhabitants by definition are the Norm (you can’t have an Other without having a starting point with which to compare it!). But what does that do to the readers, performers, and audience members? When those people enter this inside world, they bring some of their own outside experience to it, which can either poison it or enrich it. By performing this play an inside world is created that is both inside and outside of the performers, but that becomes an inside world that the audience must enter from the outside in order to experience, bringing themselves their own outside world of experiences – again, possible poison, or not. And yet the world created becomes Inside for the audience as well; when they leave, they go back Outside – literally! – to re-join the world outside of the building, a world which knows nothing of the levels of inside and outside that have been created here. It is no coincidence that this play takes place inside of a circle, broken, which encloses the performers whose own individual circles have to overlap and crash into one another and attempt to remain whole. It is that tension – and the breaking of that tension and all of those circles – that forms the backbone of this play.

In lieu of closing commentary on these issues, I offer the following anecdote from a memoir that Gorky wrote about Andreyev for that volume; Gorky is “I”, and Andreyev is “he”. Emphasis in italics is mine.

“And suddenly he started, as though burned by an inner fire. ‘One should write a story about a man, who all his life, suffering madly, searched for truth. And, truth appeared to him, but he closed his eyes, stopped his ears, and said, ‘I do not want you even if you are marvelous, because my life, my torments have ignited in my soul a hatred for you.’ What do you think?’ I did not care for this subject. He said with a sigh: ‘Yes, first one must answer, where is the truth – in man or outside of him? According to you, it is in man?’ He laughed. ‘Then this is very bad…”