Maksim Gorky was one of Andreyev’s contemporaries, and arguably the best-known Russian prose writer of the early 20th century. His full name was Aleksei Maksimovich Gorky, but he was known as Maksim, though I’ll refer to him on a last-name basis from now on. He was one of the founders of the Socialist Realist movement, which by 1934 had evolved to a form composed of four parts: 1) Proletarian: art relevant to the workers and understandable to them; 2) Typical: scenes of everyday life of the people; 3) Realistic: in the representational sense; 4) Partisan: supportive of the aims of the State and the Party. (I confess: that was paraphrased from Wikipedia.) He was a well-known revolutionary, more liberal in his leanings and generally more politically active than Andreyev, and he wrote frequently about the poor, concentrating on the great inherent worth and liveliness of the individual human being. He lived in exile from 1906 to 1913 due to health reasons and increasing government oppression of writers, but was allowed to return thanks to a grant of amnesty. His 1936 death is a contentious subject; those ‘in the know’ claim that he was killed by Stalin’s secret police, but Stalin himself denied this, even making sure that he was one of the pallbearers at Gorky’s funeral.

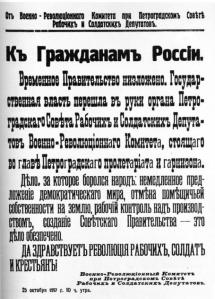

A photograph of Gorky:

James Woodward opens Leonid Andreyev: A Study with the sentence “With the exception of Gorky, Russian prose writers of the early twentieth century have received scant attention in the West. When Gorky, with his usual modesty, acknowledged the inferiority of his own artistic gifts to those of his friend, he was simply reiterating an opinion long held by most contemporary critics and literati, symbolists and ‘realists’ alike. Moreover, the general prevalence of this view, indicating that both camps found something to applaud in Andreyev’s works, suggests that in certain important respects he may be considered a more widely representative figure than Gorky of Russian literary and intellectual life of the two decades before 1917.” Thus, even though it seems that everyone up to and including Gorky and Andreyev themselves knew that Andreyev was the better writer, Andreyev still ended up in Gorky’s shadow.

As early as 1902, Andreyev was quite aware of and thankful for Gorky’s assistance with his craft; he noted that Gorky helped him become more critical of himself as well as realize his own gifts and talents. Their relationship was not always smooth; as in any professional collaboration that also happens to be personal, they had their share of disagreements, no matter how indebted Andreyev remained to Gorky. When Gorky left Russia in 1906, he went to the Isle of Capri, inviting Andreyev to join him. Andreyev finally did so in 1907, but he described the experience of sharing a dark, humid villa with Gorky as one of the most trying of his life. He was dogged by thoughts of suicide, and wrote to Gorky later (in 1912) that during their stay together he wondered if he should perhaps sever all ties with Gorky then and there. Andreyev did eventually emerge from his funk and begin writing anew with a fresh onslaught of ideas.

Before he left Capri, Andreyev began work on the story “Darkness”, with which Gorky took great issue. The story is based on an incident in which one of Andreyev’s revolutionary acquaintances lectures a prostitute on morality; offended, she slaps him, and contrite, he kisses her hand in apology. According to Gorky, Andreyev distorts this incident into an implausible tale, perverting it beyond all hope. Andreyev defended his right as an artist to spin the incident as he saw fit, but Gorky (as stated in his memoir about Andreyev) felt keenly that “from that time on… something snapped between Andreyev and myself.”

Part of the writers’ relationship was collaboration on various literary journals. In 1916, the newspaper Russian Will was started, and its principal organizer announced that, among others, he planned to have both Gorky and Andreyev write for it. Gorky refused to participate, and Andreyev agreed to edit the literary, critical, and theater sections of the paper. He mostly agreed for financial reasons, though he did sincerely believe that it was a progressive paper and that he would be allowed decent freedom in his editorial decisions; neither of those turned out to be true, and he was quickly exhausted by constantly defending himself from criticism. He fled to Finland within two years of the paper’s birth, seeking refuge from an increasingly oppressive government in which he received no support – financial or otherwise – from Gorky.

While in Finland, Andreyev read with horror the reports of other writers going bankrupt and selling all of their possessions, and then begging Gorky for work, which Gorky gave to them. Reading this, Andreyev was disgusted, seeing Gorky not as a champion of the writer’s cause but as “a friend who has gone over to the enemy” – someone to whom he referred with “passionate indignation”. Gorky sent an emissary to Finland to offer Andreyev work – two million rubles’ worth, which is not by any means a small sum – which Andreyev immediately declined.

Andreyev died in 1919 of a heart attack, and before his burial, his coffin was stored in a chapel on the grounds of a house that Gorky had stayed in five years prior. Upon hearing the news, Gorky “remarked with tears in his eyes: ‘However strange it may seem, he was my only friend. Yes, the only one…’”.

The critic Frederick White in Memoirs and Madness, however, offers a different take.

White claims that the very thing James Woodward was doing above – that is, concentrating on the literary and political differences between Gorky and Andreyev that he says led Andreyev to be blamed for the failure of their relationship – is the wrong approach, and that much more important is Gorky’s own inability to “deal with people who could not play the role he assigned to them” combined with Andreyev’s great emotional neediness.

White outlines Gorky and Andreyev’s relationship as writers as Woodward has traced, adding that in 1911 Andreyev tried to reconcile with Gorky, but Gorky responded negatively, and though the two tried time and again to patch things up in the following years, they never succeeded. Andreyev’s agreement to edit Russian Will was the nail in the coffin of their friendship, as its ideas directly opposed those of the journal Gorky was editing – The Chronicle – and Andreyev at that point considered Gorky a literary enemy. (It’s here that Andreyev moves to Finland, where Woodward picks back up.)

White then goes on to discuss Gorky as an emotional entity – he grew up with a great degree of self-reliance, so he was often emotionally distant and “did not deal well with weakness or pessimism in other people”, which Andreyev immediately sensed and was often shocked by. Andreyev grew up “craving praise and acceptance” from others, which Gorky sensed and looked upon with disdain – but not at first, when he took Andreyev under his wing and helped him develop as a writer. Gorky was thrilled to have ‘discovered’ Andreyev, and Andreyev was ecstatic at having the help and praise of his new friend. “Gorky’s belief in Andreyev’s talent”, writes White, “was the one constant in their relationship”, but Gorky later came to regret that Andreyev never reached his full potential – most likely because Gorky himself thought he lacked talent such as Andreyev’s, and his protégé’s failure was doubly so his own failure. Andreyev was constantly thankful to Gorky for his patronage, but Gorky’s emotional distance caused Andreyev to wonder if Gorky was interested in him for his talent alone, or for something closer to friendship. As early as 1902, Andreyev was writing letters to Gorky claiming that he didn’t feel they were friends, begging him to accept him as more than just a pupil, pleading for emotional support; Gorky pulled away, stating a desire to only relate to Andreyev in literary terms, thereby setting the stage for an emotional coldness that would ultimately lead to the demise of their relationship.

By 1904, many had viewed Gorky and Andreyev as tutor and pupil, but when Andreyev published the story “Red Laugh” that year, White writes that “he… stepped out of Gorky’s shadow [emphasis mine] and established himself as a literary figure… This shifted the balance of power between the two writers”. Andreyev still sought Gorky’s opinion on his work, but was more willing to publish things against which Gorky protested for one reason or another.

White somewhat agrees that the time Gorky and Andreyev spent on Capri together led to the end of their friendship, but he argues that no single event led to a distinct fissure between them. Andreyev sensed that his emotional neediness was to blame for the separation, and that Gorky wouldn’t or couldn’t give him support, even though he constantly wrote to Gorky asking him for it.

Andreyev, then, sensed that they were both “ ‘too different’ in what each wanted from their relationship”, but Gorky couldn’t take any responsibility for this himself, casting Andreyev as the sole contributor to their separation. In his memoirs of Andreyev (published in 1922, three years after Andreyev’s death), Gorky likens Andreyev to a child when speaking of his depression and suicidal tendencies, and calls him a lazy and uneducated writer who got by on his talent alone. (Andreyev had a law degree from Moscow University and a very different – that is, much less regimented and much more sporadically manic – work ethic than Gorky.) Gorky goes on to paint a rather unflattering picture of Andreyev, calling him cruel for inflicting his emotional problems on others and accusing him of pretending to be suicidal so that others would reassure him that he was a worthy person. Thus, White says, was Gorky completely unable to grasp Andreyev’s deep depression and emotional issues; Andreyev laid himself bare, and Gorky never understood him – or even admitted to never having understood him.

Recall the quotation above from Gorky about Andreyev being his only friend. White says that “Gorky felt justified in making the argument that he had been Andreyev’s good friend. He had recognized Andreev’s talent and tried to encourage the use of this natural gift. It was Andreyev’s laziness, pessimism, and disrespect for the literary trade that had brought their friendship to an end. Gorky never seems willing to accept that Andreyev may have needed the emotional support and kindness of a friend, rather than the grimace of a disapproving older brother. For Gorky, Andreyev’s literary concerns represented the limits of his friendship.” Indeed, Gorky notes at the end of his memoirs about Andreyev that when they met in 1916, they could “only speak of the past; the present erected between us a high wall of irreconcilable differences. I shall not be violating the truth if I say that to me that wall was transparent and permeable. I saw behind it a prominent original man who for ten years had been very near to me, my sole friend in literary circles. Differences of outlook ought not to affect sympathies; I never gave theories and opinions a decisive role in my relations with people. Leonid Nikolaevich Andreyev felt otherwise. But I do not blame him for this; for he was what he wished to be and what he was capable of being – a man of rare originality, rare talent, and quiet courageous in his quest for truth.” Nonetheless, White notes, it was his overall tone of damnation that led Gorky’s memoir to be the text by which critics remembered Andreyev, which unfortunately explains the scorned obscurity in which he laid for decades.