Y. Dmitriev in The Circus in Russia notes that like the theater, the circus began in public squares for the enjoyment of the common folk. This dates back to the early 11th century, when Russia was a newly-christened country, so the art form has a long and storied history there indeed. An attempt to adequately address the entire millennium of Russian circus history is beyond the scope of this particular project, so this post will concentrate on the circus contemporary to Andreyev.

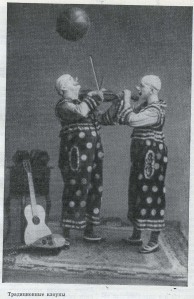

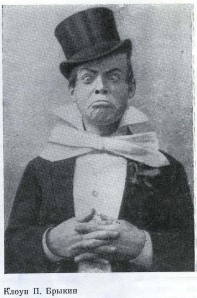

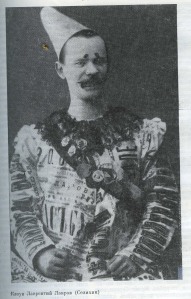

Clowns at the end of the 19th century tended to be joke-tellers more than anything else, since they possessed little to no proclivity (or capability) for physical feats. (Sample joke: Clown cries. “Why are you crying?” ask his fellow circus-folk. “How can I not cry, when after a long and difficult illness my aunt…” he pauses. “Died?” “No, got better.” This dark humor isn’t exclusive to clowns, though.)

Eventually they evolved to be more musical, and more physical, especially during Andreyev’s time when artists began to be censored. Censorship did not exclude circus performers and clowns, an as their jokes fell by the wayside, they concentrated on the more ‘traditional’ aspects of clowning that are familiar to modern audiences. Yet there was still an edge of the forbidden in their work; clowns in Moscow continued to tell political jokes knowing full well the punishment for offending a government official who might have happened to be in attendance.

In 1905, circuses started kowtowing to Tsar Nicholas II, and soon became known as vehicles of bourgeois art; the very word ‘bourgeois’ was scorned, so anything bearing that label was shunned. The circuses became watered-down, in a sense, and pursued “clean entertainment”. By 1913, the journal Organ was asking in editorials why audience interest in the circus was falling.

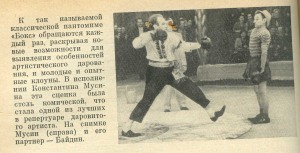

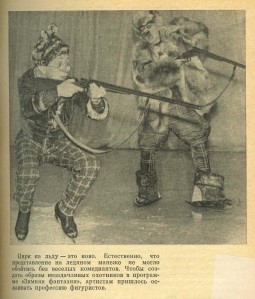

While audience interest in the circus was falling, the intelligentsia’s interest in the circus had just been piqued. In 1909, Filippo Marinetti published some contentious articles in the Italian newspaper “Figaro”; he was a key figure of Italian futurism, and he got quite a bit of attention in Russia in 1914 when his “Manifests of Futurism” were translated into Russian. In the manifests, he agitated against war as “the only hygiene of the world”, expressing a desire to raise “love for danger”. Music halls – especially those connected with circuses – were the first to heed Marinetti’s call; they were seen as “schools of heroism”, especially circuses, because they put forth a “strong and healthy atmosphere of danger”. Critics said that the circus stunts showed the greatest character of circus art because of their daring and nerve. The intelligentsia saw this and immediately paid attention; here, perhaps, was something new and exciting to breathe fresh air into stale art. Pantomime and clowning – two things essential to the circus – interested the intelligentsia the most, since they offered the greatest opportunity to mock the regime and agitate ‘safely’. Art had to progress as part of the sweeping changes occurring across the country, and the circus was no exception.

This might explain why Andreyev chose the backdrop of a circus as the vehicle for telling HE’s story; in exploring a world of myth and fantasy, misery and beauty, pain and pleasure, he could use the circus as a setting for these risky exercises in liminality. (“Liminal” refers to a person or thing that is caught between two worlds; that space is magical in Russian culture, and imbued with all sorts of meaning and superstition. The circus might have been such a space for Andreyev, given that it is neither of the outside world nor completely apart from it.)

Wikipedia – ever that fount of well-sourced knowledge – notes: “In 1919, Lenin, head of the USSR, expressed a wish for the circus to become ‘the people’s art-form’, given facilities and status on a par with theatre, opera and ballet. The USSR nationalized the Soviet circuses. In 1927 the State University of Circus and Variety Arts, better known as the Moscow Circus School, was established where performers were trained using methods developed from the Soviet gymnastics program. When the Moscow State Circus company began international tours in the 1950s, its levels of originality and artistic skill were widely applauded, and the high standard of the Russian State circus continues to this day.

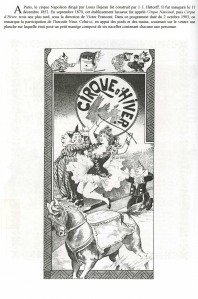

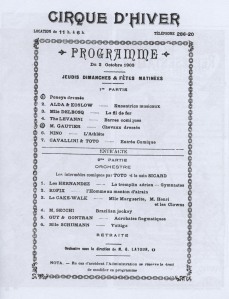

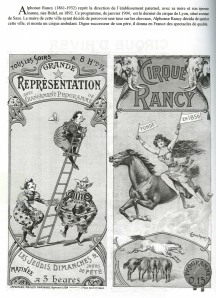

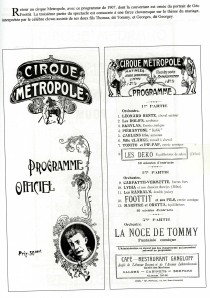

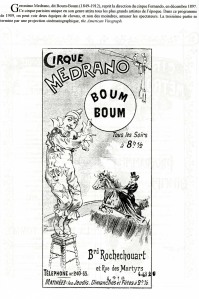

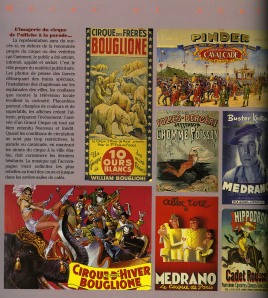

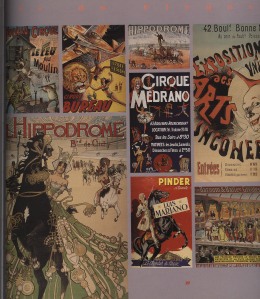

My history of the French circus is brief, especially as it pertains to early 2oth-century circuses beyond the posters and programs seen elsewhere on this site. The first ‘closed’ circus (i.e. in a tent or other enclosed space, as opposed to outdoors) was started by an Italian in Paris in 1782. Following that, French circus artists generally followed the trends of the circus in the rest of Europe, which meant that by the early 1900s their main attraction was equestrian artists. Exotic animals had been introduced to French circuses in the early to mid-1800s, but were overtaken in popularity by the equestrian acrobats in leaps and bounds. But, as the automobile began to replace the horse, the equestrian artists started losing ground to the exotic animals and their trainers, as well as acrobats, aerialists, and clowns, who had re-gained the upper hand in popularity by World War I.